On the weekend of February 14-16, 2003 more than 30 million people marched against the war on Iraq, in the largest coordinated demonstrations in human history. In Melbourne, an estimated 100,000 people (some said 150,00 and up to 200,000) joined the biggest peace march seen in Melbourne to protest against a war on Iraq. The rally started outside the State Library, made its way along Swanston Street and finished at Federation Square, clogging city streets for more than three hours.

While it did not dissuade the Australian Government at the time from engaging in the Iraq war, those who took part (including myself) believed that it was important to gather and to protest about things that really matter in our world. And always with a commitment to non-violent protest.

That protest rally stands in a great tradition of protest to bring about social, economic and political change.

During the summer of 2020, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of the police set off one of the largest mass mobilizations in US history, as hundreds of thousands of people protested against systematic racism under the banner of BlackLivesMatter (BLM). This movement was overwhelmingly nonviolent.

The recent Gaza Peace Pilgrimage (Feb 14th) was one of 96+ walks in 15 countries around the world as part of the global Gaza Ceasefire Pilgrimage over Lent, walking the distance from Gaza City to Rafah (in this case, Merndah to Melbourne/Naarm CBD), stopping for prayer at a variety of churches along the way, as well as with Jewish and Muslim friends who are also calling for a lasting ceasefire. The walk culminated at St Paul’s Cathedral at 6pm, where the pilgrims were welcomed as part of the Ash Wednesday service.

This coming Saturday, 16th of March, there will be a protest rally in Melbourne – “No AUKUS! No War! PEACE!” at 1 p.m. outside the State Library. It is part of a broad movement for peace and a nuclear-free Australia.

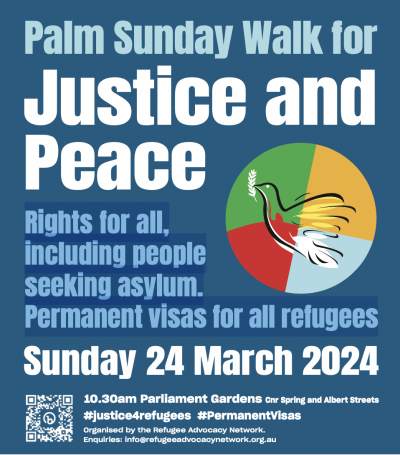

As we approach Palm Sunday (and the Palm Sunday Walk for Refugees on March 24th, starting at 10am in Parliament Gardens), it’s worth thinking about that first Palm Sunday procession.

As we approach Palm Sunday (and the Palm Sunday Walk for Refugees on March 24th, starting at 10am in Parliament Gardens), it’s worth thinking about that first Palm Sunday procession.

If someone had told me as a child that the Triumphal Entry was actually a subversive act – much more a protest than a parade, a party, or an impromptu worship service – I would have recoiled. I was accustomed to a Jesus who desires worship. Not to a Jesus who calls for peaceful but risky engagement against real-world injustice.

But according to New Testament scholars Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan, the Triumphal Entry was just such an act of intentional protest. Jesus was not the passive recipient of impromptu adoration on Palm Sunday. Though worship might have happened along the way, it was not the point. Rather, Jesus’ parade-by-donkey was a staged joke. It was an act of political theatre, an anti-imperial demonstration designed to mock the obscene pomp and circumstance of Rome.

In their compelling book, The Last Week: What the Gospels Really Teach About Jesus’ Last Days in Jerusalem, Borg and Crossan argue that two processions entered Jerusalem on that first Palm Sunday; Jesus’ was not the only Triumphal Entry. Every year, the Roman governor of Judea would ride up to Jerusalem from his coastal residence in the west, specifically to be present in the city for Passover — the Jewish festival that swelled Jerusalem’s population from its usual 50,000 to at least 200,000.

The governor would come in all of his imperial majesty to remind the Jewish pilgrims that Rome was in charge. They could commemorate an ancient victory against Egypt if they wanted to, but real, present-day resistance (if anyone was daring to consider it) was futile; Rome was watching.

Here is Borg and Crossan’s description of Pontius Pilate’s imperial procession: “A visual panoply of imperial power: cavalry on horses, foot soldiers, leather armour, helmets, weapons, banners, golden eagles mounted on poles, sun glinting on metal and gold. Sounds: the marching of feet, the creaking of leather, the clinking of bridles, the beating of drums. The swirling of dust. The eyes of the silent onlookers, some curious, some awed, some resentful.”

According to Roman imperial belief, the emperor was not simply the ruler of Rome; he was the Son of God. So for the empire’s Jewish subjects, Pilate’s procession was both a potent military threat and the embodiment of a rival theology. Armed heresy on horseback.

This is the background, Borg and Crossan argue, against which we need to frame the Triumphal Entry of Jesus. That Jesus planned a counter-procession is clear from St. Mark’s account of the event. Jesus knew he was going to enter the city on the back of a donkey; he had already made arrangements to procure one. As Pilate clanged and crashed his imperial way into Jerusalem from the west, Jesus approached from the east, looking (by contrast) ragtag and absurd. His was the procession of the ridiculous, the powerless, and the explicitly vulnerable. As Borg and Crossan remark, “What we often call the triumphal entry was actually an anti-imperial, anti-triumphal one, a deliberate lampoon of the conquering emperor entering a city on horseback through gates opened in abject submission.”

Elsewhere, Crossan notes that Jesus rode “the most unthreatening, most un-military mount imaginable: a female nursing donkey with her little colt trotting along beside her.” In fact, Jesus was drawing on the rich, prophetic symbolism of the Jewish Bible in his choice of mount. The prophet Zechariah predicted the ride of a king “on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” He would be the nonviolent king who’d “command peace to the nations”

I have no idea – and the Gospel writers don’t tell us – whether anyone in the crowd on that first Palm Sunday understood what Jesus was doing. Did they get the joke? Did they catch the subversive nature of their king’s donkey ride?

I suspect they did not. After all, they were not interested in theatre; they were ripe for revolution. They wanted – and expected – something world-altering. New Testament scholar N.T Wright writes that what they got was a mismatch between their outsized expectations and God’s small answer.

Jesus declared the coming of God’s reign. A reign of peace, a reign of justice, a reign of radical and universal freedom. Peace is, at its heart, a reflection of God’s reign, a reign dramatically unlike the oppressive and violent empire Jesus challenged on Palm Sunday.

The Church recognises peace as the legacy of Jesus, the ‘Prince of Peace’. True peace is of God so it involves the harmony of all people pursuing justice for all. Peace cannot exist where there is injustice, inequality between people and nations (economic or otherwise), disregard for the dignity of human persons, thirst for power, pursuit of endless profit as an end in itself, nor when there is an arms race. Ultimately, whenever there is disregard for or breach of the commandment to ‘love our neighbour’ we cannot rightly be said to have peace; not the peace God intends for us. Pope Francis has reminded us that cruelly destroying the resources of poorer nations and communities also stands in the way of true peace.

“In Jesus we are confronted with the One who uses power to lift up the marginalised, to challenge the rich and powerful, and to reject violence. Jesus is the disruptive, servant Lord.”

(Sally Douglas)

And so we march with the times… showing up to join with others in saying there is another way, and it’s not the way of war and violence, nor oppression and domination, nor the might of the dollar over against the dignity and worth of human persons. We show up to give testimony to the truth that true peace is of God and requires everyone to pursue justice for all.