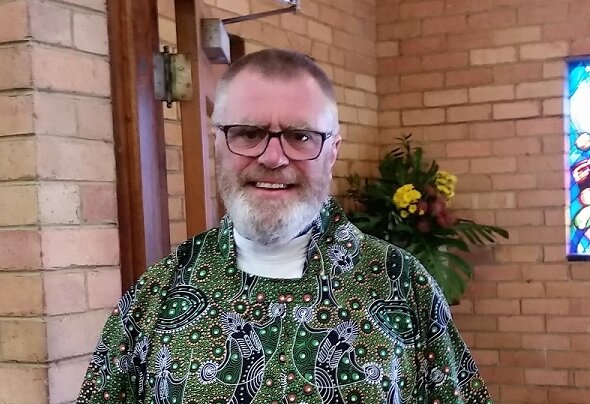

A reflection by Rev Uncle Glenn Loughrey

(Glenn is an Anglican priest and First Nations Wiradjuri Elder who worked tirelessly in the lead up to the Referendum to raise awareness of the issues. This is his reflection on the Gospel reading for Advent 2B, Mark 1:1-8)

Ain’t No Room for Peace

Today is Advent Two and our focus is on peace. What an appropriate idea to focus on in a world which is demonstrably not at peace. War, violence, conflict, and confrontation has broken out on every continent. It is broadcast to our screens, played on our radios and front page on our newspapers.

James Hillman in his book, “A Terrible Love of War” asserts that war is not an opposite state to “Peace” rather “Peace” is the brief interval before the next War. He goes further to state that war is normal, and humans need war to find meaning and purpose. He adds that belief and the Abrahamic faiths include the call for war within its language and mode of operation.

In fact, we are addicted to war. Maybe we find this confronting. We can accept, perhaps, that this is true of the Old Testament but the New Testament Is about love and the Prince of Peace. Surely, it is not about war and the language of war. Or is it? Perhaps we have recruited the language therein to mask the violence and love of war we harbour in our battle with evil, evildoers, and those unlike us.

In the recent debates around the referendum there was more emphasis on war and violence than on peace and reconciliation. Those who say they were for such values exhibited a love of violence. I spent most of my time in church communities and I can assure you the passion for violence was as real there as anywhere. The focus on how to defeat the enemy who somehow posed a threat to society was at the forefront of most conversations. Christians didn’t seem to be any different to the aggression exhibited on our tv screens, radios on stages.

The church sees itself as an instrument of peace. We who make up the church pray for peace Sunday after Sunday. We have litanies and prayer s for peace. Hold vigils to implore God to bring peace amongst us. Yet there is no peace, and we use words of violence in conversation, Bible Studies, and sermons to condemn those who do not believe, those whose lifestyles are not ours, those that have another world view.

All the praying, it seems, is to no avail. War on both a world scale and in our personal relationships continues. In our society the need to focus on family violence reminds us war is alive and well regardless of people’s faith, beliefs or hopes. Just as charity, love, begins at home, so does war. The violence partners, children and others experience here normalises violence and allows us to agree to war.

Maybe this calls us to think about why, after 2000+ years since the coming of Jesus, we are no nearer to peace on earth than the night he was born. The call to love our neighbour as ourselves hasn’t worked. And we cannot simply say that it is because there is evil in the world, and we can’t do anything about it.

Why? Thomas Merton suggests

“We are not at peace with others because we are not at peace with ourselves, and we are not at peace with ourselves because we are not at peace with God”.

How is it possible that those who have grown up breathing the Christian ethos have failed to do so? This is not about those who go to church and identify as Christian, but the fact that the Western world is and remains embedded with Christian philosophies and morality from its very beginning. Yet we are unable to find peace with self, others, and God.

In today’s reading we encounter John the Baptist and the call for repentance, individually and as a society. Yes, we individually must find peace with God but that must be as a part of a society so that it does also. The peace of everyone is needed to make peace in the world. Peace is not an ethereal personal experience. It is what we contribute to society and the world.

Thomas Merton writes again:

“Peace demands the most heroic labour and the most difficult sacrifice. It demands greater heroism than war. It demands greater fidelity to the truth and a much more perfect purity of conscience.”

John the Baptist suggests that when he calls all to repentance and reconciliation. It didn’t happen then, and it isn’t happening now. We seem to be blind to our complicity in the war in small things which leads to our complicity in the large things.

I am not sure if what Merton calls for is possible because peace is more than prayers, and blaming the other for the wars we are engaged in, in our own lives and the life of the world. Prayer is an aspiration which Merton suggests takes much more than we are often ready to commit to, to bring about peace. John suggests the same. If you want the Messiah and a new world then you must repent, not just in words, but in a life differently lived.

In the recent Referendum we had the chance to do peace in our country. Pat Dodson comments:

“…… Australians hear the whispering in their heart and know it can only be silenced by coming to terms with the original owners of this beautiful and bounteous land. Many Australians of goodwill sense that a moment for national leadership has slipped past us and is gone”.

The war continues without peace.

Why? As Desmond Tutu said:

“There can be no future unless there is peace. There can be no peace unless there is reconciliation.”

Repentance and forgiveness are the twins who power peace. Being prepared to face the fracture in relationships allows for the offer of the hand in forgiveness. Without it, violence remains.

1960’s Anti-war activist and Catholic Priest Daniel Berrigan said that while people say “Of course, let us have peace,” (they add the caveat) ……, “but at the same time let us have normalcy, let us lose nothing, let our lives stand intact, let us know neither prison nor ill repute nor disruption of ties … ”

There is no peace because there are no peacemakers. There are no makers of peace because the making of peace is at least as costly as the making of war – at least as exigent, at least as disruptive, at least as liable to bring disgrace and prison, and death in its wake.

Peace is unproductive, production is fuelled by war. Economies struggle to survive without war or the threat of the war. The war economy is, like prisons, a reliable source of income and jobs. Nations need violence and death to find their identity in contrast to the other and to balance their books. The dead come back heroes and patriotic legends are made.

Peace provides none of that.

John Dear, another peace activist writes that

“The life of “peace” is both an inner journey toward a disarmed heart and a public journey toward a disarmed world. This difficult but beautiful journey gives infinite meaning and fulfilment to life itself because our lives become a gift for the whole human race. With peace as the beginning, middle, and end of life, life makes sense.”

Peace can not be welcomed through prayer and the intervention of a benevolent God. Peace can only come when it is the central element in the lives of individuals and nations. While ever we are addicted to self-interest in all its shapes and forms, to greed and possessiveness, to demonising the unlike us, then there can be no peace.

To work for peace is something very few people are prepared to do seriously, without counting the cost. It is something the church and its members speak of but hesitate to make real. John the Baptist calls us to do a deep personal assessment and to change the way we live and be in our relationships with others despite the implications for ourselves.

John the Baptist and Jesus both attested to the consequences of peacemaking. One lost his head, and the other was nailed to a cross.

Daniel Berrigan continues:

“If you are going to follow Jesus, you better look good on wood.”