Antisemitism and Islamophobia are not the only things rupturing our communities

(published online on 18th January 2025, Sydney Morning Herald)

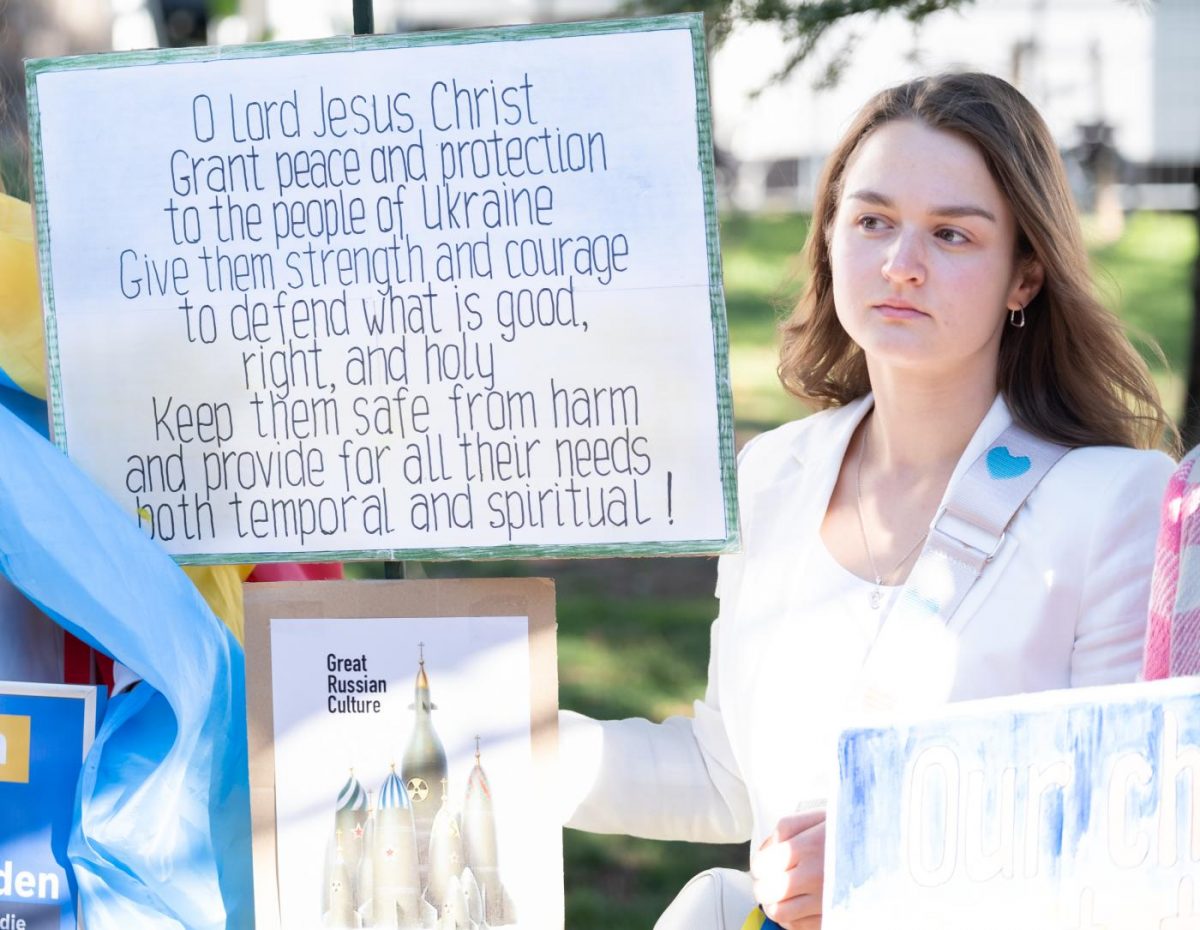

For the new year, I did something I had never done before. Rather than attend my own Protestant church, I went to a Catholic church on a Sunday morning. With the threats to social cohesion rivalling the cost of living as a defining national issue, I recognised the relative lack of opinion diversity in my own bubble. It was a small thing, but I still felt that I was crossing a line to embrace a different tribe.

That day, I worshipped in a diverse congregation made up of Caucasians like myself but also plenty of parishioners who appeared to have Indian, African, or Filipino heritage. The service was abuzz with social cohesion. The Nigerian-born priest preached a magnificent homily on how God only sees humans, not ethnicities, not skin colour. What followed were prayers for refugees, Israelis, Palestinians and Pope Francis.

Social cohesion is both a gift and a challenge. Building it requires risk, and maintaining it requires crossing lines.

We have become inured to our leaders’ words when a synagogue burns or is smeared with graffiti or when a pianist is cancelled after dedicating his recital to Palestinian victims in Gaza. We hear repetitive refrains that this is not the Australian way and this has no place here. We have become desensitised to racist rhetoric from all sides and the tragic continuing reports of innocent deaths. Most of us look away – even people like me who have been to Gaza avert our eyes from the conflict.

Hopefully, a tentative ceasefire will now bring an end to the carnage.

Rather than a good-faith public conversation, the debate has been driven by the political calculations around how one might benefit electorally from the rupture in social cohesion over Gaza. Conflict entrepreneurs politicise the conversation and then decry the breakdown in social cohesion.

For the first time in living memory, Australia’s Jewish and Muslim communities will largely vote as blocs based on Australian foreign policy. And they are being played to by our political class. Politics is driving the rupture in our communities, along with antisemitism and Islamophobia.

Peter Dutton has promised to ring Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on his first day as PM in the interests of social cohesion. However, he regularly refuses to mention Palestinians, even when praying for the situation, only mentioning Israelis.

The Greens continue to blame only Israel for the conflict in the region, refusing to acknowledge with any authenticity the evils of Hamas or the right for Israel to exist.

Meanwhile, the prime minister, wedged as he is, swings at both the Greens and the Coalition as he walks a tightrope – condemning antisemitism while calling for a ceasefire and the recognition of Palestine in order to progress a two-state solution.

Social cohesion is breaking down, but my trip to a Catholic church showed me that there can be hope. As I saw in church that day, it is not that Australians are subverting social cohesion in a vacuum. Rather, the politicisation of morality has been both embraced and toxified by our political system.

We need to reject the politicisation of suffering and cross the lines that have been drawn for us. Most of us agree that Hamas is not only barbaric but should never rule again. They should release the hostages, as they have reportedly pledged to do. And yes, they do use innocent Palestinians as human shields to protect Hamas fighters. But knowing this, we can still reasonably ask about the disproportionality of Israel killing so many human shields, particularly children.

One Jewish Australian Zionist texted me to say: “If criticism of the policies of Israel equals antisemitism, then there are a huge number of proud Jewish Zionists like me who are consigned to that category. It is appalling.”

We need Arab Australians to say they understand the existential fear of Australian Jews in the face of rising antisemitism. Equally, Australian Jews need to understand the immense suffering of Palestinians and the existential crisis for those still living in the occupied territories and with no path to hope. It is not either/or, but both/and.

Holding Israel to account for its actions is not antisemitism. Condemning Hamas to non-existence is not Islamophobic. A two-state solution is neither.

If we want to rebuild social cohesion, we must embrace nuance. And nuance requires more than what politicians seem capable of giving us.

Muslims and Jews on the ground are showing the way and crossing the line. I am so proud to be a patron of Project Rozana, made up of both Israeli Jews and Palestinian Muslims who, even in the conflict, have continued to work together to provide medical assistance in both Gaza and the West Bank. They retain their political views, but politics and politicians do not determine their actions. Human suffering that is ethnically and religiously blind in the conflict does, and they cross lines every day to help.

Let’s start crossing the “either/or” line of supporting only one side and assert justice for both. The conflict in Gaza is now one step closer to ending, but as Pope Paul VI said, “If you want peace, you must work for justice.”

Tim Costello is a senior fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity.